Wills with a self-proving affidavit attached are easier to prove valid in probate court.

A will is a document in which you name the people (or organizations) who will receive your property at death. If you have young children, you also can name the person you want to be their guardian. State laws require witnesses to watch you sign the will and to tell the probate court that you signed the will. A "self-proving" will allows the probate court to accept the will's validity without calling the witnesses to court.

- What Is a Self-Proving Will?

- How a Self-Proving Will Works

- What Are the Legal Requirements for a Self-Proving Will?

- State Rules on Self-Proving Wills

- Sample Self-Proving Affidavit

- What Are the Benefits of a Self-Proving Will?

- What Happens If a Will Is Not Self-Proving?

- How Do You Write a Self-Proving Will?

- What Are Some Alternatives to Self-Proving Wills?

- Learning More and Getting Help

What Is a Self-Proving Will?

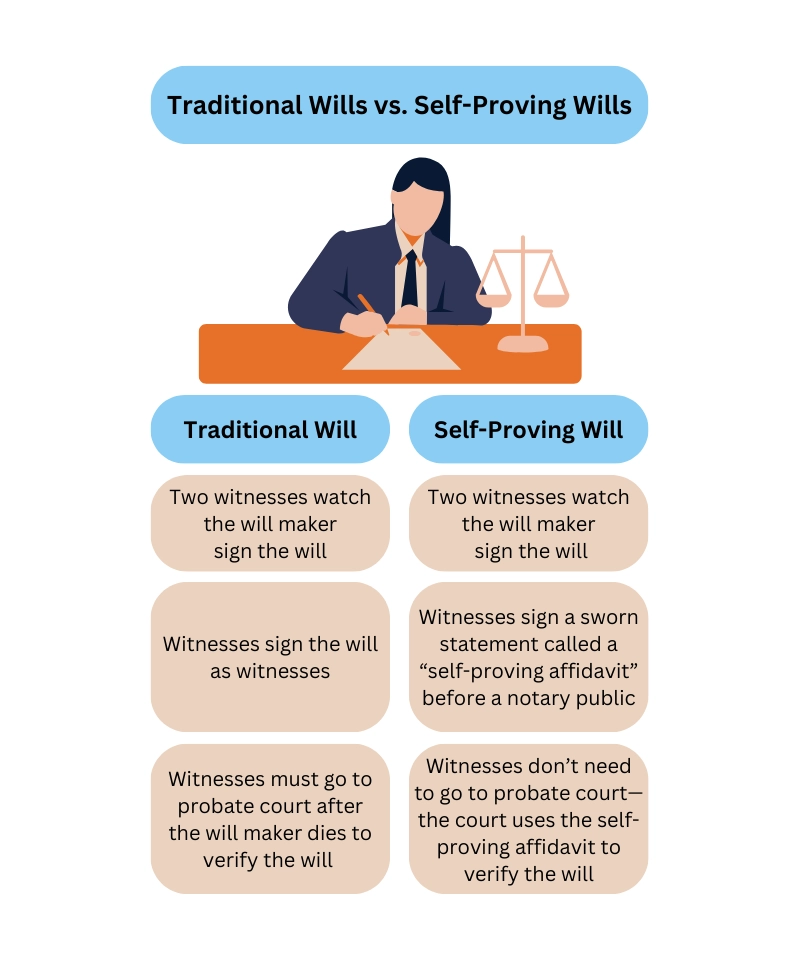

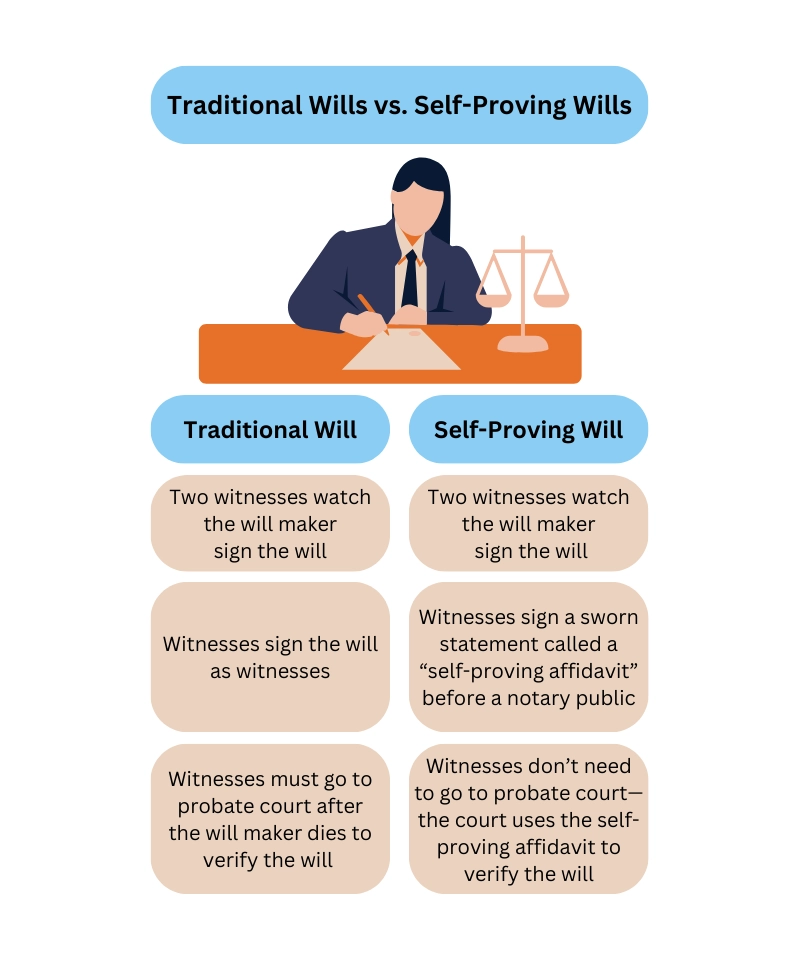

A self-proving is a will with a sworn statement (called a "self-proving affidavit") attached. In most states, a will must have two witnesses sign a statement that they watched the will maker sign the will.

A self-proving affidavit is an additional step that helps prove the will's validity to the probate court. To make a self-proving affidavit, the will maker must have a notary public present with the two witnesses. The witnesses will sign a sworn statement (see the sample self-proving affidavit below) in front of the notary who will then notarize the document.

How a Self-Proving Will Works

When people die, their property usually goes through a court procedure called "probate." During probate, the probate court will ensure your property is distributed according to the terms of your will. In your will, you'll also name an executor–the person who manages your estate during probate. If you didn't make a will–or the court determines your will is invalid–then the court will use state law to decide who gets your property and who will be your executor.

If there's a dispute about the validity of a contract or a lease, the people who signed the document can testify in court about the genuineness of their signatures. But, if there's a dispute about a will in probate court, the deceased will maker can't appear to testify that the will is valid. So there has to be another way to prove the will's validity.

That's why witnesses are crucial to proving a will. Traditionally, after someone died and the will was submitted to the probate court, the court required two adult witnesses to testify that:

- they saw the will maker sign the will

- the will maker told the witnesses the document was the will maker's will,

- the will maker appeared to have the mental capacity necessary to make a valid will, and

- the will maker appeared to be acting freely.

In some states, a witness can't be an interested party (someone who inherits under the will or would inherit under intestacy laws). Even if your state allows interested parties to be witnesses, it's generally wiser to avoid using interested parties. You also should not use witnesses who aren't of sound mind. Probate judges might reject a will if they believe the witnesses were incompetent when they signed the will.

Self-proving affidavits eliminate the need for witnesses to go to the probate court to tell the judge that the will maker signed the will. In most states, probate courts will accept the affidavit as evidence that the will is valid.

What Are the Legal Requirements for a Self-Proving Will?

In most states, the statement must be notarized—that is, signed in front of a notary public, who also signs the document and stamps an official seal on it. A few states, however, allow witnesses to sign a statement "under penalty of perjury." A notary doesn't have to be present, but the witnesses state that they are making a truthful statement—and that if they aren't, they realize they are committing the crime of perjury, or lying under oath.

If you're making a self-proving will, it's important to follow your state's requirements for a self-proving affidavit. If you don't follow your state's laws, a probate court might not accept your self-proving affidavit. In that case, the court will require your witness to affirm that you signed the will in their presence.

State Rules on Self-Proving Wills

Not every state allows for self-proving wills. In the District of Columbia and Ohio, the self-proving option is not available.

In addition, in California, Illinois, Indiana, Maryland, and Nevada, it's not necessary to take extra steps to make a will self-proving. Simply having the witnesses sign the will under oath is enough to admit the will into probate.

Sample Self-Proving Affidavit

Below is an example of a self-proving affidavit. This is only an example to help understand what is included in a self-proving will. If you are creating your own will, make sure the affidavit you use is specifically tailored to your state laws:

We, _______ and_______, the witnesses, sign our names to this instrument, being first duly sworn, and do hereby declare to the undersigned authority that the testator signs and executes this instrument as the testator's will and that the testator signs it willingly (or willingly directs another to sign for the testator), and that each of us, in the presence and hearing of the testator, hereby signs this will as witness to the testator's signing, and that to the best of our knowledge, the testator is 18 years of age or older, of sound mind, and under no constraint or undue influence.

("Testator" is a legal term for the will maker.) Typically, witnesses sign the self-proving affidavit at the same time they sign the will itself, immediately after watching the will maker sign it. But many courts will accept an affidavit that was signed later.

What Are the Benefits of a Self-Proving Will?

It can be difficult (and sometimes impossible) to find the witnesses to a will years or decades after the will maker signed it. And, if you can find them, it might be a struggle to get them to come to court or to sign affidavits describing how they watched the will being signed those many years ago–assuming they even remember the will signing.

That's why the self-proving affidavit is so important. The will maker's loved ones won't need to spend time and money trying to find the witnesses. Probate can be stressful for a deceased person's loved ones. A self-proving will eliminates a potential cause of stress.

What Happens If a Will Is Not Self-Proving?

If you don't have a self-proving will, it doesn't automatically mean that the court will reject your will. As mentioned above, if your will isn't self-proving, your witnesses can tell the court that it's your will and that you signed it. However, if you don't have a self-proving will and no one can find your witnesses, the court likely will reject your will.

If the probate court rejects your will, then it will proceed with probate as if there's no will at all. When there isn't a valid will, a probate judge will use state intestate succession laws to determine who gets your property. These laws generally give all your property to your spouse and children first. If you don't have a spouse or children, then the court will give your assets to the next closest relatives–usually starting with parents and siblings before moving on to increasingly distant relatives. If the court can't locate any relatives, then the state will get your assets.

How Do You Write a Self-Proving Will?

If you want to create a self-proving will, you can hire an estate planning attorney or do it on your own with a form or a do-it-yourself program.

Using a Lawyer to Make a Self-Proving Will

A lawyer isn't always needed to create a simple will with a self-proving affidavit. If you have significant assets or a complicated family situation, you likely will want an estate planning attorney to create your will. A lawyer can ensure that your will complies with your state's laws. Using an attorney might make the process easier because many lawyers have a notary public in their offices–or at least have a service they usually use–so you won't need to find one on your own.

A lawyer also can prepare other documents you might need, such as a living trust, powers of attorney, or a living will.

Making a Self-Proving Will on Your Own

If you decide to write your will yourself, you can purchase software that helps you write the will or you can use an online form. Many state statutes include sample language for wills and self-proving affidavits. Your state courts' website or local probate court website also might have forms available. Be careful to use a form that's designed for your state and that's provided by a trusted source.

If you use a software program, ensure you use one for your state. The program also should have a self-proving affidavit as an option. Some programs have options for you to create other estate planning documents like trusts and health care directives. To make a will that includes a self-proving affidavit for your state, try Nolo's Quicken WillMaker & Trust. You also can use WillMaker to create other estate planning documents.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Whether you use a lawyer or make a will on your own, you should make sure you avoid common mistakes when drafting a will. One common mistake is to use a form will from an unreliable source or a template that's not tailored to your state's laws. If your will doesn't comply with your state's laws–for example, not having the right number of witnesses or correct language for a self-proving affidavit–then it might not be enforceable.

Another typical error is failing to review and update a will. You should review your will every few years to make sure it still reflects your wishes. You might need to update your will if you have children, marry, divorce, or have other life events that change your wishes. Failing to account for these life changes could result in the wrong people receiving your property after your death.

If you make a will and hide it where no one can find it, then you will have wasted the time and money you spent creating it. Make sure you let trusted people know where your will is. Some estate planning lawyers will store wills for clients. If that's not an option, you could let your executor or a trustworthy friend or family member know where you've stored it. Finally, it's generally a bad idea to put a will in a safe deposit box because banks often make it difficult for others to access them.

What Are Some Alternatives to Self-Proving Wills?

If you're trying to make a will that will allow your witnesses to avoid appearing before the probate court, attaching a self-proving affidavit is your safest option (if your state allows self-proving wills). Some states might have ways to admit a will if both witnesses have died, but why take the risk if you can create a self-proving will?

Another way to avoid needing witnesses to appear in court is to avoid probate altogether. There are several ways to try to avoid probate, such as living trusts and beneficiary designations, but you should still have a will in case any of your assets aren't covered by those probate-avoidance techniques.

Learning More and Getting Help

To get more free legal information about wills, go to the Wills section of AllLaw.com. To get more information about other estate planning topics, visit the Wills and Trusts section of AllLaw.com.

If you have significant assets or your family situation isn't straightforward (or you're uncomfortable making your own will), consider getting help from an experienced estate planning lawyer licensed in your state.

- What Is a Self-Proving Will?

- How a Self-Proving Will Works

- What Are the Legal Requirements for a Self-Proving Will?

- State Rules on Self-Proving Wills

- Sample Self-Proving Affidavit

- What Are the Benefits of a Self-Proving Will?

- What Happens If a Will Is Not Self-Proving?

- How Do You Write a Self-Proving Will?

- What Are Some Alternatives to Self-Proving Wills?

- Learning More and Getting Help